I Ching

The Book of Changes for Modern Readers

by J. H. Huang and Carolyn Phillips

coming soon from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins

An encyclopedia of oracles, based on a mythic view of the universe

that is fundamental to all Chinese thought.

—Joseph Campbell

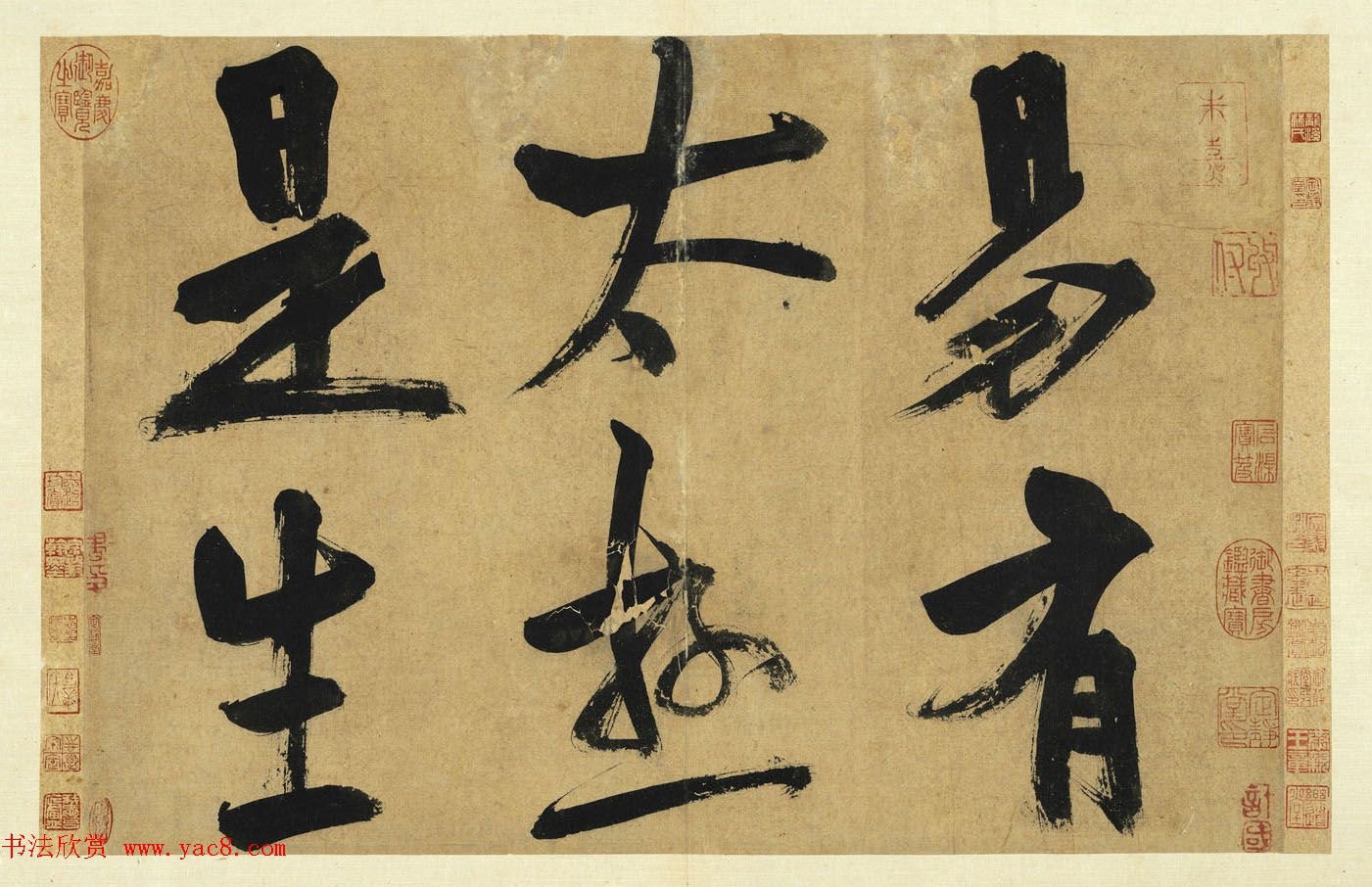

One of the world’s oldest written works, the I Ching (also known in English as The Book of Changes, the Yijing, or simply as Changes) is considered a vital cornerstone of Chinese philosophy. This is the first and most important classic of the Confucian school.

The I Ching was first written down around 3,000 years ago, but its origins are much more ancient. Its extreme age has therefore—at least up to now—made this one of the most difficult books to read, much less digest, even in the original Chinese.

The ancient Chinese mind contemplates the cosmos in a way comparable to that of the modern physicist…. Just as causality describes the sequence of events, so synchronicity to the Chinese mind deals with the coincidence of events….

Even to the most biased eye it is obvious that [the I Ching] represents one long admonition to careful scrutiny of one’s own character, attitude, and motives.

—Carl Jung

Its teachings have seeped out over the centuries to influence both the West and the East in fields as varied as:

o philosophy

o religion

o science

o mathematics (including Boolean algebra)

o computer science, and

o quantum mechanics,

as well as literature and the arts.

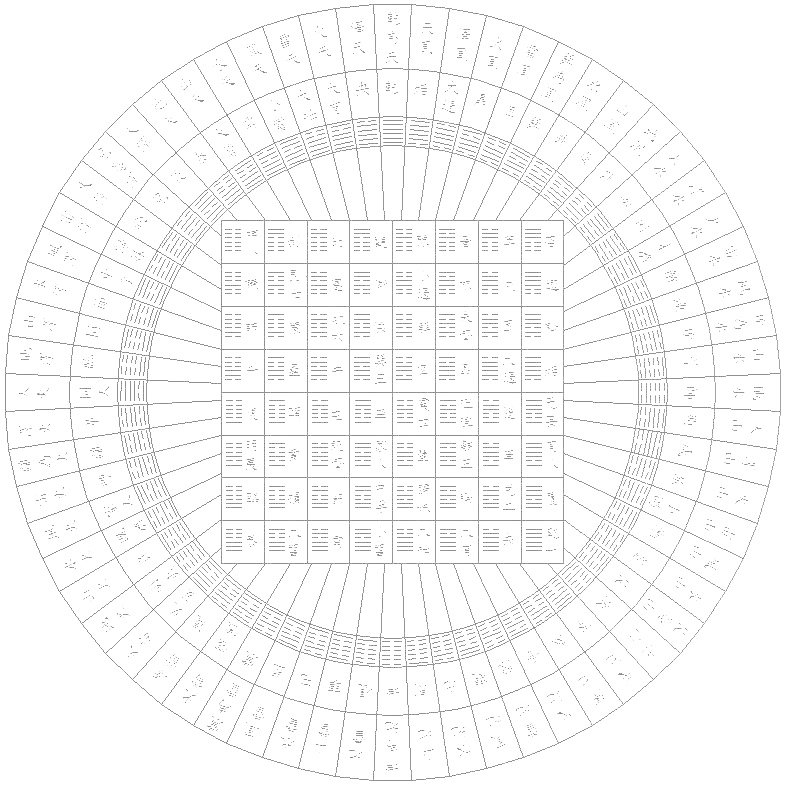

The I Ching is composed of 64 hexagrams (six broken and unbroken lines arranged in a block), and these hexagrams have been used since time immemorial to divine the future and offer sage advice. These lines represent the yin and the yang: the duality of things as small as our personal existence and as large as the cosmos.

Most important of all to our modern lives, its universal language of yin and yang has been transformed into the binary code composed of endless combinations of 0s and 1s by which all computers are run.

Considering how few Chinese classics have ever been properly rendered into a Western language, it should come as no surprise that the I Ching has never been accurately translated into English. The version that most Westerners refer to even today was released in 1924 by the German missionary Richard Wilhelm; its 1950 English edition stands out in particular due to its forward by renowned psychoanalyst Carl Jung.

However, the Wilhelm translation is so filled with errors and misunderstandings—and is so utterly incomprehensible—that readers have only been able to guess at what this book was trying to communicate. The fact that it has still managed to influence so many people in the West is therefore not a testament to the translator, but rather to the inherent power and wisdom of these ageless words.